I loved it almost as much as the first one. It is the true sequel to Matrix 1. Matrix 2 and 3 are largely non-necessary for the story arc (although I love them too in their own peculiar and awkward way). For an alternate perspective on the necessity of Matrix 2 and 3, see the blog of my friend and Biblical scholar, Dr. Brian LePort.

Like all of the Matrix movies, it had too much exposition and functioned like a comic book trying to teach philosophy. And I enjoyed every second of it. Comic book fans don’t want philosophical exposition, and those who style themselves deep intellectuals don’t want their pure discourse within ten miles of anything as course as pop culture. But as a low rent aficionado of both pop culture and ideological analysis, I loved the attempt to put both together for the masses (of which I am most definitely part of).

It was a great apologetic for Transhumanism in which humans will only be able to fully evolve by embracing and even embodying technology to enhance our natural endowments. It also demonstrated the idea that some system of ordering reality and society is needed. The original Matrix could have been read as a polemic advocating for anarchic individualism (“Live outside the box! Overcome the Man!”). Yet pure anarchy is impossible and empty, and libertarian individualism leaves no room for community. Healthy life, in all its facets, is a dance between structure and freedom.

It was a helpful re-visioning of a Buddhist-Christian Gospel of liberation and compassionate return. It put that story of creation, lostness, redemption, enlightenment, and resurrection into new clothes so that postmodern people might be able to hear and see the Gospel afresh. To illustrate this, it is helpful to remember the basic symbolism. Thomas Anderson is Neo, and in order here is the symbolism of his names: Thomas is a reference to "Doubting Thomas" whose faith was transformed by an encounter with the resurrected Jesus. Anderson literally means "Son of Man", which is a title for Jesus Christ. Neo means "New One", or "New Man", which is a reference to being made new through spiritual rebirth. Thomas Anderson as Neo realizes he may be the "Chosen One" to redeem the human race from bondage after he is referred to as "Jesus Christ my own personal savior" in the first movie.

Neo is enabled to become the Chosen One by the Love of his fellow rebel Trinity. Her name of course refers to the idea that God, the Ultimate Source of Reality, is a Threefold Dance of Love within the One Divine Being. And in the first trilogy, her love and kiss literally brings Neo back from the dead, resurrecting him. In the final movie, we learn that Neo and Trinity form a symbiotic life-- much as the Incarnate Jesus Christ is the Earthly embodiment of the Divine Life of the Holy Trinity-- and only in connection with each other can they save the world. Even Trinity's "false name" of Tiffany is an anglicized version of "Theophany": A manifestation of God. And this is just a catalogue of the super-obvious Christian references in the film, not to mention the more obscure references to Christianity, Buddhism, and other spiritual paths. For instance, Neo follows the Path of the Bodhisattva because his compassion leads him to turn back from ultimate withdrawal from the world, in order to come back into the world, to bring hope and enlightenment to others.

I also loved the redemptive arc of Agent Smith (the “Satan” of the original trilogy). He has a kind of reconciliation with Neo and Trinity, and even helps them in their struggle. Thus, by the end of Matrix 4, everyone can be the Chosen One if they realize it, yet also Agent Smith can be anyone and happen in anyone. The best and worst of alternatives are open to every person at all times, because we are all saints and sinners at the same time. But the ultimate hope is that whole world can eventually be healed and reconciled by love, including all persons whether they are organic or machine. And if you wait to read the film’s dedication at The End, the ultimate victory of creative and redemptive Love is plainly written! In all of this, there’s also a strong theme of Jungian reconciliation with one’s dark side leading to wholeness. All part and parcel of the Gospel that really is Good News for all.

I actually enjoyed how the fight scenes deconstructed themselves into an almost unwatchable orgy of chaos, and the over the top zombie swarm attacks that made the viewer say “awwww this is just too much!” A great visual representation about how "the myth redemptive violence" can never bring about the world we most deeply desire. As someone very Wise once said: Those who live by the sword die by the sword. And this is as true for civilizations as it is for individuals.

Along these same lines, but not in a good way, is the cameo of the Merovingian and his henchman. They were kinda ridiculous and I wonder why they were added in. But maybe they were a commentary on how a society built on violence banalizes the high culture represented by the Merovingian. Because that scene was definitely the most banal in the movie (with a strong second place going to the human zombie bombs during the swarm sequence).

Matrix 4 did a great job of outfoxing and outflanking the critique of the Matrix being too “meta” by making it every form of meta that is imaginable. It was almost like the filmmakers anticipated the critique of being overly meta and decided to drown the critics in meta. But this also led into a powerful commentary about how “the System” takes every form of opposition to it and commodifies it to make it part of the System so it makes those trapped in the System immune to genuine critique of the System.

The Company name is Deus Machina: God is the Machine. God is the totality of the System. Nice juxtaposition with the idea of Deus Ex Machina, in which something transcendent pierces the System to bring new life and meaning into it. Both the fatalistic inevitability of Deus Machina and the hopeful release offered by Deus Ex Machina are necessary for the story of the Matrix.

Speaking of which, there was some great commentary on how stories form our identity, our memory, and our sense of reality. Along with this, there was good commentary on how humans tend to value feelings over facts, and cherry pick facts to fit the narrative of our feelings. And we do this until the weight of totality of actual facts finally causes our narrative of feelings to buckle and implode so that we are able to view reality in a different way.

It did great work on showing how the Coinherence of Opposites is necessary for wholeness in individuals and in societies. The male needs the female. The mathematical needs the aesthetic. The mundane needs the transcendent. The machine needs the person. The system needs the individual. And vice versa. Binaries are overcome and synthesized as Spectrums. Hegel would be proud.

Another great move came in using The Analyst as the embodiment of medicalizing non-normal conscious states in order to control and sublimate the insights gained from those states. When someone systematically deconstructs and questions status quo reality and power dynamics, ancient cultures called them “seers” and “prophets”. For the last two centuries we have silenced them as “crazy” (although, as the Analyst points out, we no longer directly call people “crazy” so we can plausibly deny we are silencing them with this label).

I also loved the juxtaposition of how commitment to the status quo can undermine our purpose and meaning in life, whether that is the status quo of war at all costs, or the status quo of peace at all costs. To everything there is a season and a time for everything under Heaven: A time for war and a time for peace.

Along with this, there was a great commentary on how constant noise, constant activity, and constantly running the “hedonic treadmill” halts personal growth and stops us from becoming our authentic self. We need time for remembrance and “being” and even boredom to become our true self.

This movie can also be read as an apologetic for BOTH metaphysical idealism AND metaphysical materialism. Materialism posits that material conditions are ultimately real, and they give rise to the superstructure of ideas and culture through the Marxist conflict of material forces. We see this in how the Earthly conflict between humans and machines gave birth to the virtual un-reality of the Matrix. Idealism posits that ultimate reality is more like “mind” and “math” than it is like material stuff, and it is consciousness and mathematic patterns that constitute physical reality. We see this in how the stability and solidity of the Matrix is actually a function of sentient algorithms upholding reality itself, and this in turn signals the audience that our everyday reality is constituted in the same way. Yet, both of the diametrically opposite possibilities of materialism and idealism are plausible interpretations of the Matrix. Much like how we read Hegel. And like how we read Reality itself.

As the movie points out about itself, it can be read as a crypto-anarchist critique of the Capitalist system: From the fact that Corporations are the ultimate "bad guys", to the commodification of humans into sheeple who literally power the System, to the anti-capitalist band Rage Against the Machine providing the finale song. However, reading the Matrix as merely anti-capitalist isn’t that simple. The phenomenon that is the Matrix media franchise can only be brought to fruition in society that has a highly developed market for entertainment and technology: That is at least partially Capitalist. Thus the critique the Matrix brings to Capitalism can only exist within a Capitalist system. So, perhaps the point being made about Systems of Control is broader than just one socio-economic system. Perhaps it is a point that when any System becomes totalizing and all-encompassing, it becomes self-perpetuating and parasitic at the expense of those it was originally created to benefit. The response is not so much to destroy all Systems, as it is to create balancing and mutually antagonistic systems which can never claim totality, which in turn allow for open spaces of individual expression and creativity.

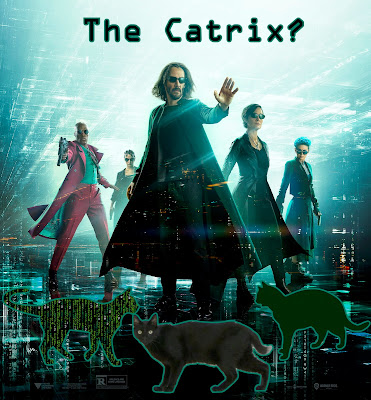

If something like the Matrix is real, this is the perfect movie to make people think it is too meta and unbelievable to be real. It is either too good to be true, or too bad to be true, depending on one’s view. But if nothing like the Matrix is real, this is the perfect movie to make people think it might actually be real. It is a Parallax view of a movie. Or perhaps a Schrödinger's cat of a movie. And speaking of cats…

After all the appearances of the Black Cat, and the Catrix post credits scene, I wonder if the Black Cat— that ancient symbol of Chaos— is the true Engineer and keeper of the Matrix. Black Cat spoken aloud sounds exactly like Black Hat, which is a kind of computer hacker which finds holes in the system and spreads chaos. It could be that Black Cats are reminders that we need Black Hats to help us hack the mundane systems of control that keep us from becoming all that we could be.

No comments:

Post a Comment